‘I’m trying to capture the pulse of what is happening somewhere in real time.’

(Photo by Scott Beale/Laughing Squid)

As the Arab Spring swept through North Africa and the Middle East, Andy Carvin (@acarvin), the senior social media strategist for NPR, tweeted the news from his home near Washington almost without rest. His Twitter feed covered the breakout rebellions in Tunisia and Egypt, their spread to Bahrain, Libya and Yemen, and the ongoing tragedy in Syria. In the process, Carvin developed ways to enhance the journalistic value of social media, scouring online tweets and videos for the best sources providing the most trustworthy information. In his new book, “Distant Witness: Social Media, the Arab Spring and a Journalism Revolution” (CUNY Journalism Press, 2013), Carvin describes his journalistic breakthroughs and evokes the human dramas that he covered daily. The following excerpts of his conversation with Mikhael Simmonds were edited for length and clarity.

Do you consider yourself a journalist?

Do you consider yourself a journalist?

Yeah, I do consider myself a journalist, but I’m also somewhat leery about defining who is a journalist and who is not, because I think many of us who have no experience in reporting have the capacity of creating journalism either when the muse strikes them or the opportunity strikes them. Random acts of journalism happen all the time and they’re not always conducted by professional journalists.

You say on your Twitter profile that you’re a professional Information DJ. What do you mean by that?

That kind of started as a joke. For the last two years people have really struggled to describe exactly what I do. I struggle to describe what I do. I’m not necessarily creating products, news products out of my work. Instead, I tend to be online a lot and I’m trying to capture the pulse of what is happening somewhere in real time. I don’t remember who it was, but someone described what I did as something like what a DJ does. I have access to real-time information. I choose what gets spun out at any given moment, and it’s my responsibility to decide if it’s something that my audience is going to be able to react to or not. One can easily argue that what I’m doing isn’t really that different from what a news host or presenter does on a live broadcast. They are being given large amounts of information by staff in their news studio and they’re working with producers and editors to sort it out in real time. Then they present it to the public live in a way that ideally creates a compelling narrative. Essentially I’m trying to do the same thing. I don’t have the studio and I don’t have the staff working with me for the most part, but instead I have my Twitter followers and they work with me as volunteers to help me figure out what’s going on.

In the book you have people from Syria, from Egypt, and they’re all cross referencing each other. How do you go about making sense of all this “music?”

Well I generally use a lot of Twitter lists. And I use Twitter client software like Tweetdeck or Hootsuite or one of these tools that allow you to set up individual columns for specific topics.

At the height of the Arab Spring, if you leaned over my shoulder, you would see at least half a dozen of these columns across my screen. One for Yemen, one for Syria, one for Libya. Depending on which one was being more volatile that day, I would move the columns around to make sure they were in my sight lines. Over time I was also able to determine who in these countries, or related to these countries, seemed to have the best information. So I also I created what you may call a greatest hits Twitter list of people representing all these countries.

When did you have time to sleep?

During part of the Arab Spring I was online up to 18 hours a day. I would be checking Twitter at 6 a.m. while having breakfast. I would be checking Twitter before going to bed just before midnight, and I was on most of the time in between. Somehow I managed to actually get sleep in between and so I was able to keep this pace seven days a week for months and months on end. You know there is a certain level of adrenaline rush that goes on when you are covering a story that’s very dynamic and you know it’s history in the making. I think part of it had to do with the fact that for e a country like Egypt, it’s not unusual for the protest to begin after afternoon prayers, which was around one in the afternoon their time, that time of year. So when I got online at 6 a.m., generally speaking, I hadn’t missed much in Egypt yet because they were just getting started. For other places like Libya and Syria, because the fighting has been so much more intense in those places – it’s 24 hours a day – there is no way I can choose the right hours and capture everything I would want to. I just have to accept the fact that I can’t do everything. I’m not a robot.

Do you think what you do in social media undermines traditional news?

I don’t think it undermines journalism. I think it’s a part of journalism. Historically, there have always been situations where reporters are unable to get to a place and are still expected to report on it. Reporting on stories remotely isn’t new to journalism. What I think is new here is that you don’t have these bottlenecks of information flowing to the public anymore. I mean, if you think about the word media it comes from the Latin word for the middle. Journalists are essentially middlemen between information about what’s going on in the world and the public’s appetite for it. And what social media has done is it allows people both caught in the action of the news story or interested in the news story to do an end run around traditional media sources and interact directly with the people on the ground. I like to try thinking of what I do as really complementing what happens in mainstream media. Look at the countries I focus on, like Syria, for example. I am able to do a lot trying to authenticate videos, find new sources, tell stories of people over the course of time. But I also work with colleagues at NPR who risk their lives all the time sneaking across the border and visiting hotspots across the country to tell stories in a ways I never could. So, if you’re on the ground covering a story you can tell very compelling emotional, powerful stories through your presence there and your ability to look a person in the eye and interview them. I can’t accomplish that with the type of reporting I’m doing. But there are other things I can accomplish. I am able to interact with many more people in real time, and I’m able to intermix parallel stories. I am able to get feedback from the public in real time and integrate it into how I tell stories. They’re just different ways of reporting. I don’t think one undermines the other. I think they complement each other and I’m proud to be doing this, working at a mainstream media organization that takes its reporting on the ground very seriously but also encourages new forms of journalism.

You have access to many different media tools. Why did you decide to present your story in the form of a book?

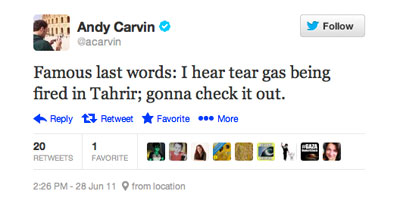

I did this for myself, really. Initially, I was using the tool Storify to capture some of the methods I had used in some of the stories or to recall certain incidents such as the battle in Tahrir Square. And as I was doing this – like in April, May, June 2011 – it became clear to me it was getting harder and harder for me to find the source material from social media that was just a few months old at that point. Social media can be very ephemeral. It’s very hard to do deep searches on the Internet for stuff that’s even a few month old. So I kind of felt that there was a window of opportunity for me to capture these stories and organize them in such a way that we won’t forget them. It’s not unusual for people to publish diaries and memoirs after a war or after a revolution. [But] this is really the first series of conflicts where participants are able to share these stories while they’re happening. You can feel and hear and see their stories in real time and you can actually interact with them. And it was really unlike anything we have ever seen on a scale like that before. And I wanted to see if I could capture that in written form – and also maybe turn it into a book.

What’s the future of social media and journalism?

What’s the future of social media and journalism?

Oh, who knows! If I had an answer to where this is going I would try to make a few phone calls to a few venture capitalists to come up with an idea and retire young hopefully from whatever I produced out of it. It’s so hard to predict what will happen because things are changing all the time. In terms of what stories get covered, I think a lot is going to depend on the state of the digital divide in those locations – as well as whether there is a critical mass of experts or a critical mass of eyewitnesses who can use social media to record them. As for the tools themselves, I think there is much more of an appetite in news organizations to use social media effectively. We’re all trying to figure out how to curate this information better, how to authenticate it, how to find our sources quickly, how to do it on the run.